Because George Burke’s

appointment was political and not bound by any civil service rules, he served at the pleasure of the chairman of the Railroad and Public Service Commission (RPSC), Thomas E. Carey. A former president of the Anaconda Mine, Mill and Smeltermen’s Union, and a janitor at Carroll College and the State House, Carey had been elected in 1932 as a Democrat to the RPSC for a six-year term and promptly became its Chairman. Created by the Legislature only twenty years earlier, the Commission had been given broad powers to set the prices consumers paid for water, heat, light, railroad and highway transportation, sewers, and telegraph and telephone service. As a consequence, it had made corporate enemies. The RPSC had especially angered the Montana Power Company, whose Board of Directors was intertwined with that of the Anaconda Copper Company, which had spawned the utility in 1912.Montana Power had waged a failing campaign to block the 1934 election of a RPSC commissioner named Jerry O’Connell, a fiery advocate of reducing electricity and natural gas rates to households as the Depression deepened. In 1930 at the age of twenty-one he had been elected to the state House of Representatives. Montana Power enraged its detractors by placing negative articles and editorials about O’Connell in the biggest newspapers, which were owned at the time by the Anaconda Company. These included the Missoulian, The Helena Independent, the Billings Gazette, the Anaconda Standard and the Butte Miner, what one scholar calls the “Copper Chorus.” Critics charged that the company was passing on the costs of this smear campaign to already-burdened consumers. In a collateral effort to discredit the RPSC, its opponents orchestrated the arrest of Thomas Carey on 22 October 1934, two weeks before the election. He was charged with molesting a fifteen-year-old boy, a felony. Carey posted $1,500 in bail and was released. He denied the “vile charge” and hired attorneys to defend him in what would be a loud and raucous trial the following May.

However, dirty politics turned out to be useless against the New Deal juggernaut. O’Connell won a landslide victory and immediately began voting to set lower rates for vital utilities. In February 1935 he and Carey ordered Montana Power to drop its minimum $1.25 monthly fee for natural gas, charged to residential consumers whether they used any gas or not, and invited the company to make up for significant lost revenue by raising the rates on large commercial consumers. They slashed the rates consumers paid for water in Butte and Thompson Falls. In doing so they overrode the third Commissioner, a corporate lackey named Andrew Young, whom detractors accused of wearing a “copper collar.” Montana Power challenged the gas ruling in court, claiming O’Connell was “prejudiced” because he had promised during his campaign to eliminate the charge. In the end, relief for the company from the courts was denied.

Meanwhile, Tom Carey was ferreting out what he perceived as disloyalty among the RPSC’s employees. On 4 January 1935 he fired eleven of them. Burke and a stenographer were spared, apparently Carey’s only trusted loyalists. Burke not only survived Carey’s Friday afternoon massacre he was appointed the Commission’s new chief engineer. Like most “engineers” of his generation he had no college training. But he had learned enough fundamentals of the profession from working for the oil companies, the Ford plant in Long Beach and as the PSC’s oil and gas inspector that he could pass himself off as an engineer. His claim to this professional title was affirmed in October 1936 when he was nominated for membership into the Montana Society of Engineers. He joined fifteen other men, including Archie Bray, a ceramic engineer and patron of the arts whose Helena-based Western Clay Manufacturing Company supplied the high-quality brick used to construct hundreds of buildings across the state in the 1930s and 40s.

Before Carey’s guilt or innocence could be determined by any court, a Legislative committee condemned him by voting for a resolution calling for Montana Attorney General Raymond T. Nagle to remove him from office for reasons of “malfeasance, incompetence, and neglect of official duty.” In addition to the morals accusation, a House committee alleged that Carey had been absent from his office for two months, and had employed the services of the RPSC’s stenographer to aid in his legal defense. The late-evening, closed-door debate, according to the newspapers, “was freely punctuated with displays of disorder and near-physical combat.” The author of the Carey “investigation,” a loud-mouthed Democratic legislator from Lewistown named Herbert Haight, was the recipient of an unsigned, typewritten letter the last line of which read: “May Satan give you your just deserts and here’s hoping your life will be very short-lived.” In addition, a bill was introduced in the House that would abolish the RPSC. But it went nowhere. During the debate Representative E. R. Ormsbee of Mineral County rose to accuse the corporations of fabricating the charges against Carey in order to defeat O’Connell, and of poisoning the minds of other progressive legislators with their propaganda.

The Helena Independent published a copy of a written “confession” allegedly signed by Carey in October of 1934 after his arrest, in which he admits to allowing several young boys to enter his room at the Grandon Hotel in Helena and there to “take hold of and play with his private parts.” Coming to Carey’s defense was Lewis Penwell, well-known lawyer, stockman and U.S. Collector of Internal Revenue for Montana. As the publisher of a small, rabble-rousing weekly called the Western Progressive, which railed against the corporations and the “copper collar” editors of their captive newspapers, Penwell had joined ideological forces with Carey and O’Connell in an attempt to leash Montana Power. In a statement published in a special edition of Penwell’s paper Carey claimed that the confession was a forgery. “. . . every word in that statement is untrue, the entire statement is a malicious falsehood and a vicious lie. I have never at any time spoken, uttered or written one single word contained in that document.”

He accused “predatory utility interests” of orchestrating the charges against him because he had joined Jerry O’Connell “in his fight to reduce exorbitant utility rates and save Montana from the plunder of the power trust.” On 16 May 1935 Carey’s trial began in Lewis and Clark District Court with testimony from a fifteen-year-old boy who claimed that the man invited him into his hotel room, where he made “indecent gestures.” The boy said he “broke away” and “took a swing” at the defendant before running from the room. The boy further testified that on previous occasions Carey had sat down beside him in a lunchroom and slapped his leg. Defense attorneys countered with a sworn affidavit from the boy in which he admitted never having been invited into Carey’s room nor ever being accosted by the defendant.

Testifying for the prosecution, the boy said he signed the paper while he was surrounded by defense attorneys. One of them shook his fist menacingly, the boy claimed, declaring that unless it was signed the boy would bring disgrace upon his family and perhaps a jail term for himself. The prosecution trotted in several young boys, who claimed to have been in Carey’s hotel room. Carey responded that the boys invited themselves in because they liked Carey to read them the “funny papers” and help them with their homework. He denied the accusation that he had given the boys cigarettes. During the proceedings the attorneys shouted loudly, gesticulated wildly and interrupted each other repeatedly. There were frequent references to the law books cluttering the large counsel table. Relative peace returned after Judge George W. Padbury, Jr. ordered the twelve-man jury to disregard the commotion.

Following final arguments lasting until late in the evening of 22 May the jury retired at 10:45 P.M. from the packed courtroom to deliberate. Ninety minutes later they returned to a courtroom that was nearly empty because no one had expected such a speedy decision. “We find the defendant not guilty,” the foreman announced.

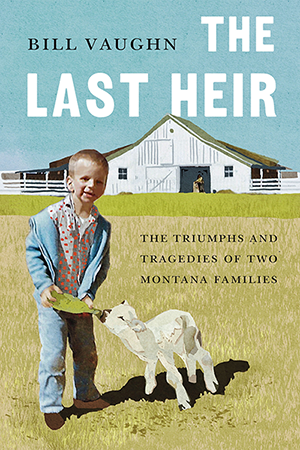

Read more about the Burkes and the Herrins at The Last Heir.